Devices and Lights That Affect Your Sleep Every Night — What Matters Before You Choose

Most Americans use screens and artificial lighting every evening, yet many are surprised when their sleep doesn’t improve even after “cutting blue light.” The reason isn’t simply screen exposure. It’s that light and devices interact with your body’s internal timing system in ways that people commonly misunderstand. Knowing which light sources actually disrupt sleep, when they do it, and why — separates guesswork from reliable results.

This article explains the real relationships between light, sleep cycles, and eye responses — and what matters when you’re choosing how to light your evenings or use your screens.

$750 Amazon Gift Card

Not everyone qualifies for this $750 Amazon gift card. Checking only takes a moment. You can check if you’re eligible.

Why Evening Light Exposure Doesn’t Behave the Way People Expect

People often assume:

- All screens damage sleep equally

- Blue-light filters are always effective

- Less time with devices late = better sleep

Yet so many still toss, turn, or wake up groggy. That’s because timing and context govern the impact, not just the presence of light. Light isn’t merely a sight signal — it’s a biological time signal.

What People Think Is Happening

A common belief is:

“Blue light from screens physically harms the eyes and directly stops sleep.”

This feels reasonable because blue wavelengths are energetic, and nighttime device use is correlated with poor sleep. It’s simple: light causes trouble → sleep suffers.

That model seems easy to apply, but it focuses on object properties (the screen) instead of system behavior (how the brain and eyes respond at night). It lumps visual sensation (seeing) and circadian signaling (body clock) together — even though they are distinct processes.

What’s Actually Happening Under the Surface

To understand sleep impact, we need to separate two mechanisms:

1. Visual processing does not equal biological timing

Your eyes have rods and cones that handle vision, and ipRGC cells that send light information to your internal clock. The latter don’t make you see anything — they inform your circadian rhythm.

Blue wavelengths matter here not because they are “bad,” but because daylight is rich in blue light. Over evolutionary time, these cells learned to associate blue-rich light with daytime.

2. Light as a timing signal, not a pain signal

When blue-rich light hits the eyes in late evening, the brain interprets it as “daytime still happening.” This delays melatonin release, shifting your sleep timing later — not because screens are harmful, but because the system reads wrong timing cues.

This circadian signal is influenced by:

- Brightness (intensity of light)

- Timing (when light is received)

- Duration (how long exposure continues)

- Contrast with surrounding light levels

Visual discomfort (eye strain) can happen separately due to glare, focus demands, and poor contrast — but that is not the same mechanism that delays your internal clock.

Why This Leads to the Observed Outcome

The combination of visual and circadian effects explains why:

- Using screens in the morning or midday often feels fine and may even anchor your sleep-wake rhythm.

- Using screens in dim evenings can push your sleep later, even if you feel visually comfortable.

- Blue-light filters or “night modes” help some people but not others, because brightness and timing outweigh spectrum alone.

- Lights with the same spectrum affect you differently at 5 p.m. versus 10 p.m.

The “same light source at different times” idea is the key mechanism most explanations miss.

How This Works in Practice

Here’s how these mechanisms play out in everyday life:

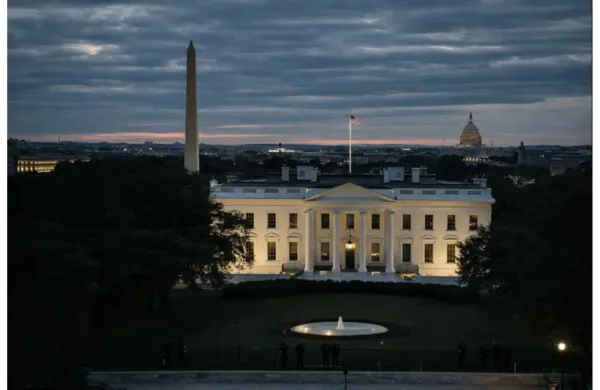

Evening indoor lighting

Warm, low-intensity bulbs create weak circadian signals. Even if these lights have some blue content, the overall signal is not strong enough to reset your internal clock — unless combined with bright screens.

Screens in bright rooms

A phone or tablet in a brightly lit room often doesn’t shift rhythms as much — the overall light signal is dominated by the environment.

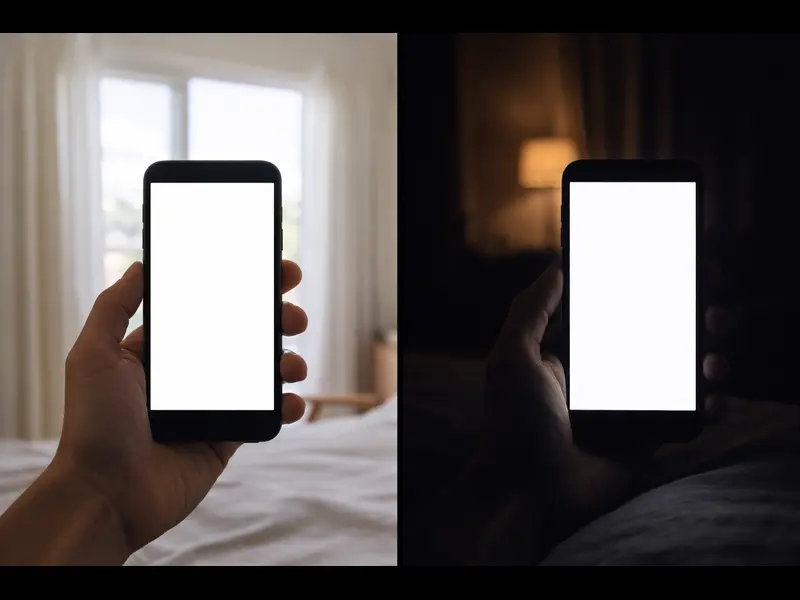

Screens in darkness

Even dim screens stand out in a dark room, creating a relative increase in circadian cue strength. Your internal clock sees this as “still daytime,” which delays sleepiness.

These patterns explain individual variation: two people can use the same device, yet one’s sleep is unaffected and the other’s is disrupted — because their lighting context and timing differ.

What Matters Before You Choose Your Evening Lighting or Screen Habits

When thinking about light and sleep, prioritize:

1. Timing over spectrum

Light before sunset doesn’t disrupt your clock the same way as light after sunset.

2. Brightness and contrast

A dim room with a bright screen sends a stronger signal than a well-lit room with a screen.

3. Context, not color alone

Warm bulbs and cool screens both exist — what matters is relative cue strength and when that light arrives.

4. Distinguish strain vs timing

Eye discomfort is about visual load; sleep disruption is about circadian signaling.

This mental model — light as information about time — lets you predict outcomes, instead of following rules that only apply in specific situations.

Real-World Scenarios That Reveal the Mechanism

Scenario: Nighttime social scrolling

A person scrolls social media in bed under dim lights.

The screen stands out — a strong “daytime” signal — delaying melatonin and pushing bedtime later, even if the screen is on low brightness.

Scenario: Morning device use

Another person checks email on a phone during a bright morning breakfast room.

The overall light environment already signals daytime — so the device’s contribution doesn’t shift rhythm significantly.

These outcomes aren’t random: they reflect when and how your biological clock interprets light signals.

Quick Understanding Summary

Sleep disruption from light isn’t caused by blue light alone; it stems from how biological clocks interpret light as information about time. Blue-rich and high-contrast light late in the evening strengthens a “daytime” cue, delaying internal sleep timing. Visual discomfort and circadian effects are separate mechanisms. Context, timing, and brightness determine outcomes more than light color alone.

Common Misunderstandings

- “Any screen use near bedtime will wreck sleep.”

→ Only relative light contrast and timing matter for circadian impact. - “Blue-light glasses fix sleep problems.”

→ They address visual spectrum, not timing cues and brightness context. - “Warm lights are always better than cool lights.”

→ Warm lights can still signal daytime if they’re bright relative to surroundings. - “Eye strain means the clock is disrupted.”

→ Visual strain and circadian delay are different systems.

$500 Walmart Gift Card

Some users qualify for a $500 Walmart gift card. You can check if you qualify.

FAQs

Does blue light damage my eyes?

Everyday screen exposure doesn’t structurally damage healthy eyes; discomfort relates to visual workload.

Will night mode modes help?

They can reduce contrast and perceived glare, but their effect on sleep depends on overall light context and timing.

Is reading a book better than a screen before bed?

Only if the lighting context doesn’t create relative brightness peaks that signal daytime.

Why do I sleep fine with movies but not with scrolling?

Movement, brightness, and contrast patterns differ, altering how your brain interprets the light as a timing signal.

Can proper lighting prevent all sleep disruption?

It helps, but individual rhythms and habits vary; lighting is one factor among several.

Conclusion — What Is No Longer Confusing

Light doesn’t “hurt” sleep in a simple, linear way.

It tells the brain what time it thinks it is.

Understanding light as a time signal, not a threat, clarifies why similar activities affect people differently and enables more informed choices.